Sitting by the sea in a lush Scottish garden, Seagazer stares at the horizon, undisturbed by the lashing winds sweeping over her. A luminous presence, radiating conviction and hope, this white, impeccably-chiseled figure is so powerful, it’s easy to be enveloped by a sublime calm. To stand there, to reflect, to feel the glow. Transforming inanimate sculpture into animate, sensual renderings is a rarefied talent. It hints of an alchemy only found in the gifted hands of a few, the likes of Rodin, Michelangelo, Henry Moore, and Brâncuși.A Hungarian storyteller with a distinct language, and purity, Boldi is compellingly demanding entry into this pantheon. He does so with grace, fantasy, and audacity, a verve which spurs him to provocatively illuminate such complexities as Genesis, the stars’ enlightening radiance, and gazing towards the infinite.

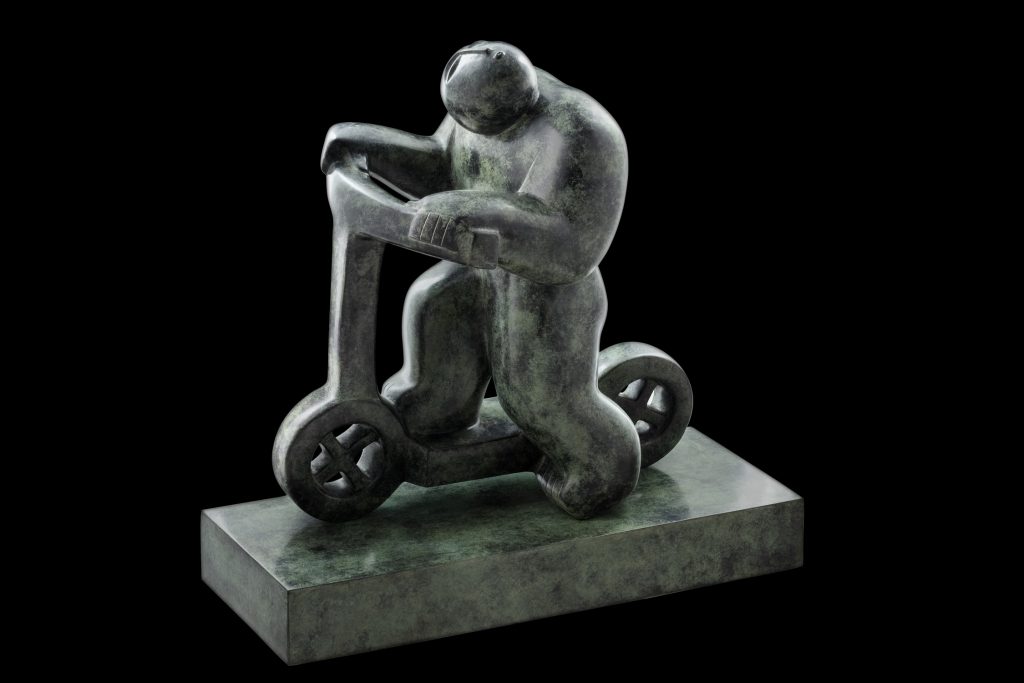

“Capturing eternal qualities, that’s what I hope to do, universalities , delicate and meaningful emotions,” explains Boldi, 50, his wife Johanna interpreting as he further describes his quest for the “immutable.”Pointing to a slab of raw white Carrara marble, the Italian Loni stone used by Michelangelo, Boldi continues, “Art must be lasting. I am trying to find harmonies that are enduring. I love classical music, the wonders of Nature, the perfection of the human form. If I am successful, I bring emotions, a sense of timelessness.” Renowned for his rounded and chubby sculptures, Boldi has long been fascinated by the essence of stone, its “messages”–how Nature speaks to us, and reveals endearing simplicities. Growing up in a household with a passionate appreciation of art (his great-great-grandfather Ödön Lechner was an acclaimed architect in the 19th Century), he’d wander in the countryside, collecting stones eroded by a river. “Soft” and “rounded” stones captivated him, influenced his future interpretations of the human body.

“My grandfather, all of his splendid buildings, especially his beautiful roofs, they too had an impact,” recalls Boldi, reverentially, surrounded by unfinished bronze and marble works in a studio just outside Budapest.“Nature, seeing birds flocking to those roofs…just wonderful. I still love birds, I hike a lot, and am always looking at stones.”Starting to work with clay at age 12, Boldi went on to study Fine Arts in Vienna, Budapest, and at the prestigious Master School of Fine Arts at Pannonius University in Pecs, Hungary. He ultimately won five scholarships that led to the sculptor’s Mecca, Carrara. There it was thrilling to walk in the footsteps of Michelangelo and Rodin, to handle marble once quarried by the Ancients. Yet recalling his early stays in Carrara (one was on his 1998 honeymoon), Boldi laughs, “I had money for stone…food? I ate a lot of pasta.“It was a difficult time for me in the beginning. Very hard! Going to Carrara was still a new life, great to start statues there, and to learn. I formed many important relationships there that taught me so much…that led to future exhibitions (one with painter/sculptor Pietro Cascella in Rome, then the Hague, Budapest and elsewhere). Carrara, my trips there…so many memories…”

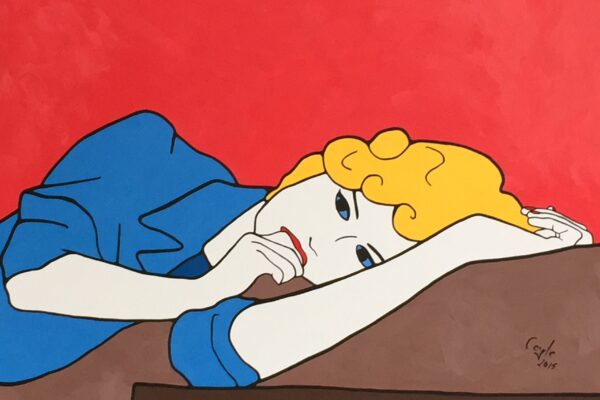

The cachet of white Statuario, marble used for the Pieta, clearly fascinated him. So did Brâncuși. Famed for his seemingly “endless” curves and columns, this Romanian rebel had abandoned the traditional “representation” of Nature in the early 20th Century. He instead emphasized spiritual effects, revealing the “invisible.” “The high priest of modernism,” known for minimal aesthetic of surface, Brâncuși paved a path for Baldi and his gentle, delicately-rounded forms. Many of Boldi’s works look upwards, and he’s bent on expressing provocative, profound emotions, especially in such works as Theatre, Mother with her Child, Boy’s Head, and Sitting Archer. As French graphic designer Laetitia Lagoutte observes, “(his work) puts forward woman in the pure state…in all that she is…Woman in her excellence as at the time of the Paleolithic when Venus symbolized motherhood, fertility and life.”Propelled by empowerment and freedom, Brazilian Woman explicitly exults the sensual feminine mystique. Like many of his works, it’s tantalizingly provocative, a head languidly bent back, eager to be caressed, to be comforted. Denying any intended sexuality. Boldly insists, “the women in Brazil are free…extremely beautiful,” and adds, “I love the tactile nature of sculpture. I want all my works to be touched.”

He’s clearly the introspective sensualist, inspired by theatre, the kinetic movement of a bird soaring over rooftops, and the rapturous interplay between a man and a woman. Avoiding “major statements” and instead allowing our imaginations to roam, Boldi suffuses Concerto with youthful innocence, plus a decorous hint of sexuality. It is also jazz, a juxtaposition of competing forces, flaunting an airy weightlessness that spins him and his hands towards the next surface, the next sensation. Fallen Warrior II prompts us to be even more reflective. It is anguish, a melodic cry for peace by a warrior weakened by strife. Yet there’s a nobility here, a stretched-out figure summoning the strength to be revitalized. The sculpture is not a polemical work. Boldi shies away from political statements. “I am only telling stories,” he insists. “I am only trying to echo a man’s plea for a better world.”In that bold search to capture the “immutable,” Boldi never accepts commissions. He simply waits for multi-layered ideas to incubate, abstracts waiting to be translated into characters, shapes that convey new migratory avenues for our imagination. He too is an explorer. Undeterred by the expense of marble or bronze, the prospect of a mistake being ruinous, he’s constantly reshaping, refining, experimenting.

Excited by the challenge of inventing “a totally new patina,” Boldi spent 15 years trying to compose a distinctive bronze surface. He finally collaborated with chemists to discover the desired feel and finish.“It was an arduous trial and error process working with acids,” declares Boldi. Detailing how the effort culminated in a 2000 Paris exhibition, he eagerly continues, “ finding beauty is often difficult…getting the right (Aristilde Maillol) patina, that was difficult. I wanted to be very delicate. When I create a sculpture it’s for me, and must be perfect.”

Genesis, his triumphant bronze and marble series, is a celebration of Creation, a tribute to Nature. He’s spent his life perfecting forms that resonate inviolable truths. Polishing Genesis for weeks, he tirelessly tried to animate the inspirational charm of a Franz Liszt rhapsody.“Poetry, music, feelings about my children, all this is my life story, what I want to express,” says Boldi, pointing to a “wonderful” painting by his 20-year-old daughter Bolda who’s attending the Hungarian University of Fine Arts in Budapest. “She is the future, new beginnings…what we badly need today…Messages of pure hope.”

By Edward Kiersh