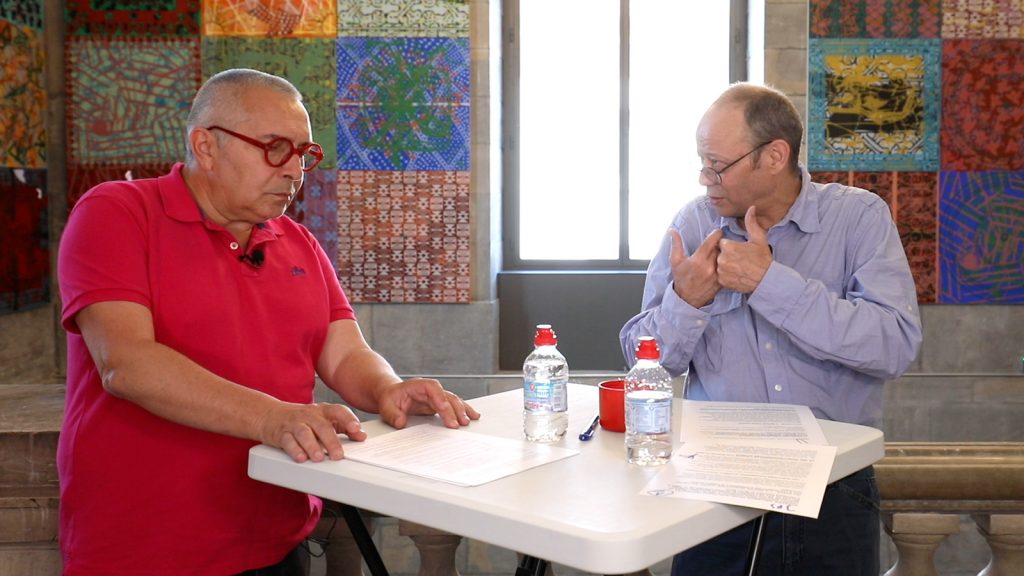

INTERVIEW-TALK BETWEEN ARTIST JEAN-PIERRE SERGENT AND ART HISTORIAN THIERRY SAVATIER IN FRONT OF THE FOUR PILLARS OF HEAVEN EXHIBITION AT THE BESANÇON FINE ART & ARCHAEOLOGY MUSEUM | JULY 2nd 2021

Transcription of the filmed Interview between Jean-Pierre Sergent and Thierry Savatier (Art Historian and world specialist of Pablo Picasso’s and Gustave Courbet’s works)

PART 1

Jean-Pierre Sergent: Hello everybody. It is July 2nd 2021 at the , which is one of the oldest museums in France, and I have the great pleasure welcoming my very close friend Thierry Savatier, We have already done several interviews; this will be the fifth one today.

Thierry Savatier: Yes!

JPS: So, it’s really a great honor to welcome you in this museum and in front of my installations that have been exhibited for almost two years now and this interview will be in collaboration with international art magazine ‘Luxury Splash of Art‘ and we will have some questions from Agnieszka. So Thierry, Agnieszka asked me: “What really attracted you to my work? What really interests you about my art?”

TS: I would say that there are two aspects in this installation that are quite interesting. The first aspect is the title “The Four Pillars of Heaven“; indeed, it invites us to think about verticality, it invites us to think about spirituality which, obviously, is in no way confused with religion, but which is a relationship with what is beyond us; then, we can call it: ‘God’, ‘Great Architect’… whatever you want, it doesn’t really matter. What is important is this notion of relationship with what is beyond us. And, indeed, we have there, as you reminded us, by the staircase that we have to climb, by the look that we will carry on this installation, this invitation to spirituality. And then, there is another aspect of the installation which is interesting, it is that the works are stuck to the wall directly, without frame! The frame, finally, is something that is supposed to embellish but which often limits; whereas here the contact is directly on the wall and it reminds me of what Picasso had wanted for his exhibition at the Palais des Papes in 1971, when he saw the works hung, he had all the frames removed, he wanted the paintings to be directly hanged unframed on the stone walls of the Palais and that had given a quite astonishing effect. I think we have the same thing here. Is it, for you, a reminder of what are, for example, the cave paintings, I think of the prehistoric caves like those of Angles-sur-l’Anglin near Poitiers or Lascaux?

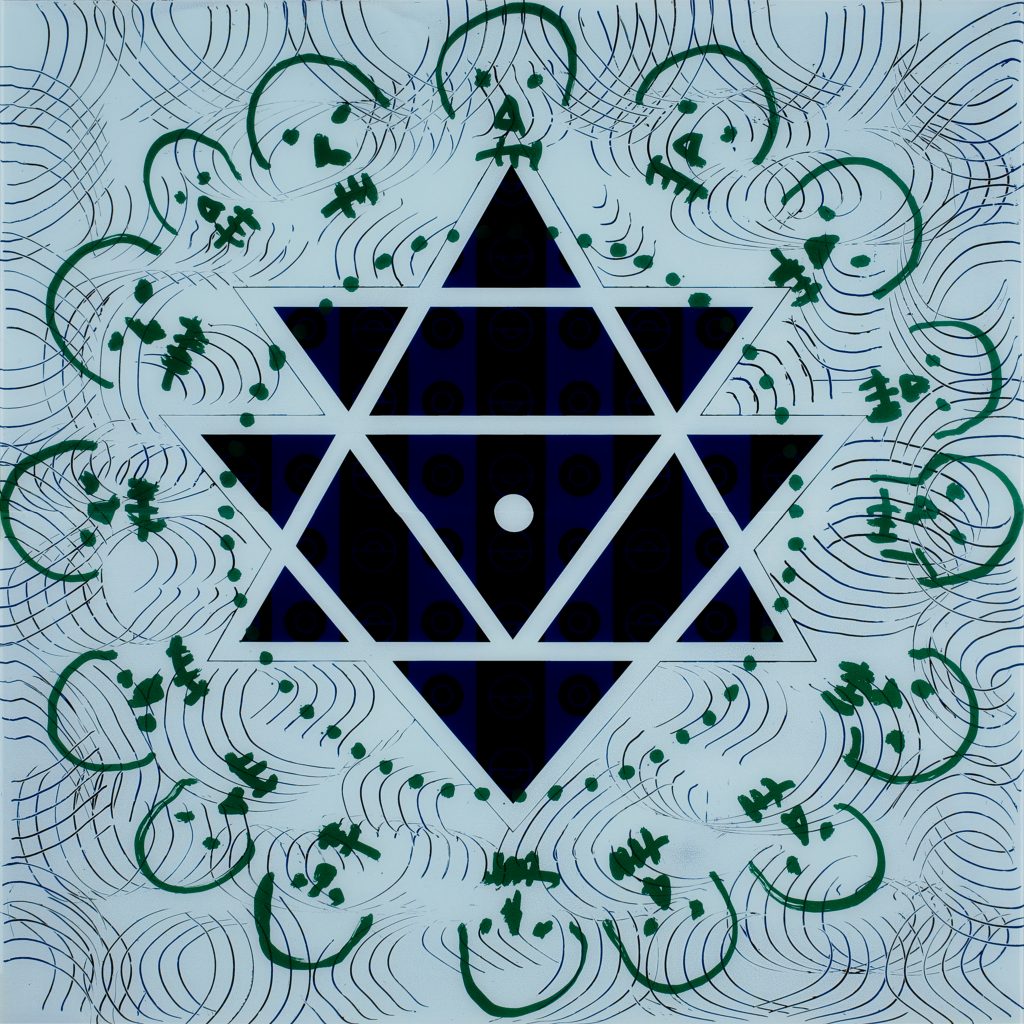

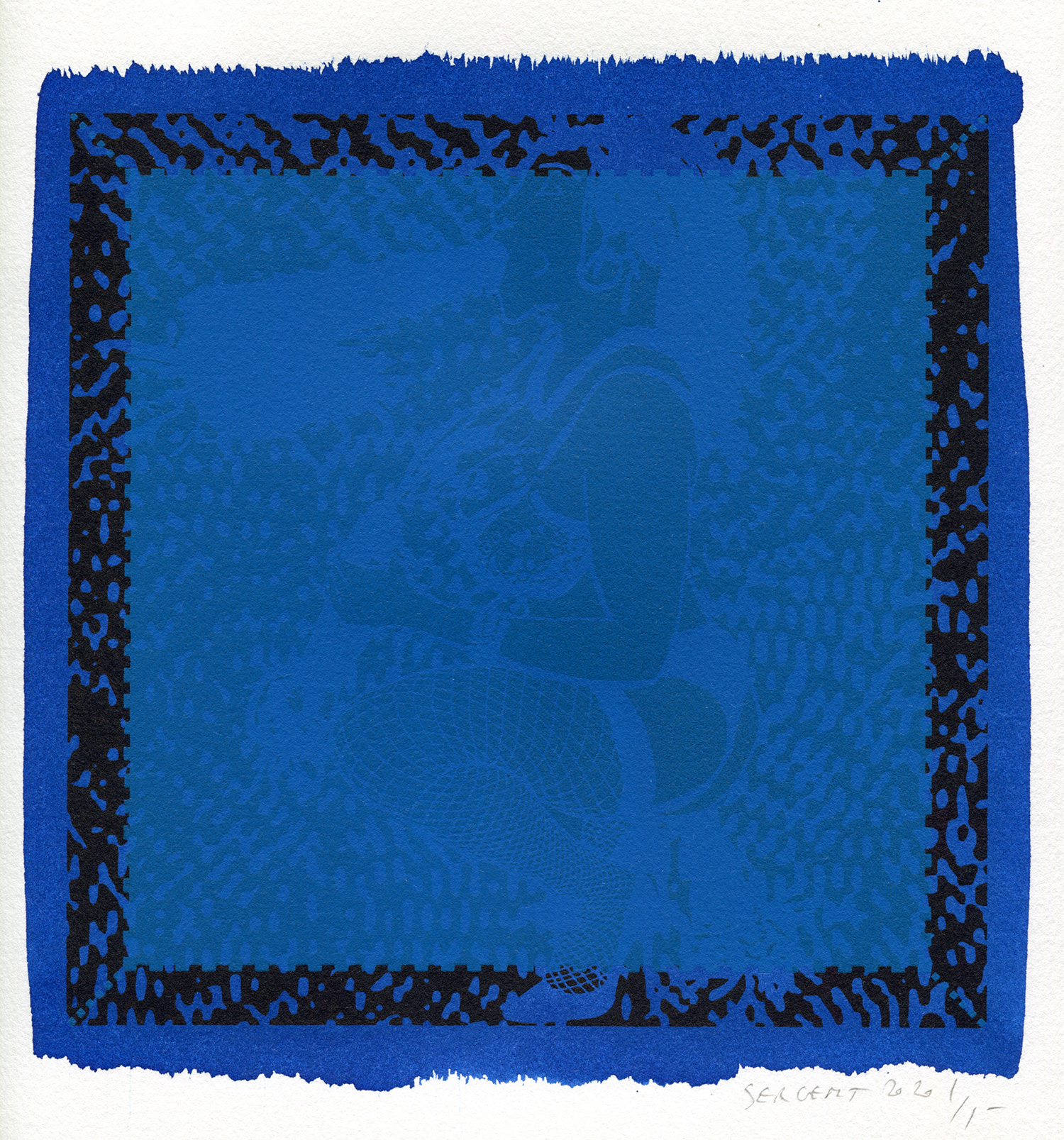

JPS: Yes, absolutely. It was while visiting the Pech Merle cave that I had this revelation; not only about the size of the work but also about the layering of my works… Because, as you can see here, I always work by accumulating several layers of images successively. In general, there are 3 images, but there can be 4 or 5, it is what is called ‘layering’ in English. That is to say, what is important also, is to leave the individual work, unique, made by only one artist to enter a kind of collective work, since we know that cave paintings have been reworked over successive millennia, so it was not necessarily the same individuals or several individuals at the same time, time dilates and expands a little in cave art and I hope that this is what we can also find in my works. I want to dilate time a little bit so that one can access, precisely, this verticality and this “pre-eternity”… it looks pretentious… But yes, I want to make a work that is part of the history of humanity, of course.

TS: This dilation of time, we see it when we observe the works, notably by the superimposition of the layers of different graphics that often belong to different eras, to different cultures, that corresponds completely to the dilation of time. And what struck me, the first time I saw these works and it continues to impress me. I see your new works, I see all this evolution; in order to understand, especially your works on Plexiglas, it is absolutely necessary to forget all the preconceived ideas that we may have and which we have inherited by our education. We are marked in the West by, at the same time, the Platonic philosophy and the Judeo-Christianity with, necessarily, these binary values which forge our judgment thus, good – evil, black – white, the primitive – the civilized, etc… And in fact, one realizes that in order to understand your works, we must above all begin by forgetting all that and apprehend each work with a new look, that requires an effort but that is fascinating.

JPS: Yes, thank you, that’s exactly it, what I want to, is to get out of the norms, obviously. Afterwards, to what extent can the artist, in his personal life, be outside the norms? It does raise a question? It’s true that it’s a bit difficult. I will quote a sentence of André Malraux in The Mirror of Limbo: “The time of Art does not coincide with that of the living.” In a way, the time of the living beings does not fit with that of Art and it is true that being an artist which is trying to make a work a little creative and a little ‘out of the box’, it is a little painful, sometimes, because the public does not follow. There is always this problem of the tricky relationship with the public. Can an artist exist without an audience? Fortunately, my work is shown here, so maybe that will move the lines a bit, but it still creates to me, an uneasiness, because we, artists, are no longer integrated into the flow of our contemporaries life.

TS: Yes, the artist needs a public, it’s true, but the artist is also aware that he is sometimes ahead of his time, when, for example, Picasso painted “The Big Pisser” which is now in the Pompidou Centre in Paris and he proposes it to his gallery owner Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, he is scared. He said no, it would be really difficult to sell, given the theme, of course, and Picasso was not at all offended and replied: “Yes, no doubt, they will understand it in 30 or 50 years…” I think that’s a bit true too, you end up understanding an art work after a certain time period.

JPS: Yes of course, but there is not only the sexual problem in my work, there is also the spiritual problem. How to apprehend a work that wants to be spiritual, that is my will, if you understand? It’s a question to ask but we don’t really have the answer!

TS: Yes, but I believe that one and the other are linked, anyway. We once talked about a question that was that Art only happens if you let the savage in: “People often think that Art is the most highly cultivated, disciplined, organized human production; yet, while it requires a long preparation, Art only happens if you let the wild one in.” The Etiquette of Freedom, Gary Snyder.

JPS: Yes, that’s right.

TS: I find it a very interesting idea because in fact, obviously, we have to define things well; for me, ‘savage’ is absolutely not a reference to Rousseau, to the ‘good savage’, which personally I have never approved of, but there is a savagery in the work of Art, and specially in the major work of Art. If we look at two examples on which I am working a lot, one is Gustave Courbet and the other one, it is Picasso, there is in Courbet savagery, in certain works. Let’s take “The Deer’s Hallali” which is presented here, in this Museum of Fine Arts, which is a huge canvas. This painting is pure savagery and if we take another work that is even more famous, it is “The Origin of the World”. It is obvious that there is savagery in “The Origin of the World”, if only in this pubic hair that reminds the viewer of the origin or the animal cousin of the human being. And then, with Picasso, we see savagery also, I think obviously in “The Young Ladies of Avignon” and there, when he paints this work, even if he exposes it only ten years later; the critic, the public does not understand, they see savagery and there is some; not only in the bodies but also in the faces and then, we see it, also, in “Guernica”. So we can see that in most of the major works of art, finally, there is always a part of savagery that is present. And I believe that in your Plexiglas paintings, for example, we see it very well.

JPS: Thank you, yes, we also feel that in Pollock’s works, this kind of cosmic ejaculation, Pollock’s work is very ejaculatory, he’s an artist that I respect of course, because I was lucky enough to live in New York for a long time and to see his work often and I wanted to quote Gary Snyder again; I’ve just read an Interview with Jim Harrison and Gary Snyder in The Etiquette of Freedom, and we get back to Western culture; he says: “I don’t like Western culture because it contains, in my opinion, a lot of mistakes that are the cause of a very old environmental crisis.” Here we are talking about environment, but we could also talk about Art, that is to say, that the initial preconceptions, the foundations, the initial prejudices were not the right ones. The religious art that was put forward, Christ on the cross, the Virgin Mary and all that, made people deeply sexually frustrated… Westerners have lost a lot! He is deeply frustrated with its own body… What is important is the body, it is the way we live our life and we must live it as fully as possible. Buddhists, Taoists, Hinduists and animists still have the discipline of experiencing their body more fully and more deeply.

TS: Yes, it’s the body and then it’s also, since he mentions the environment, and there again, we go back to the roots of Judeo-Christianity, from the starting point when, in Genesis, we are told that God created the world, the animals, Nature and then, he ends up creating man and woman and it is indicated, that Man will dominate Nature; As soon as we start from the principle that there is a domination of nature, as opposed, for example, to Confucianism, and there, your “Four Pillars of Heaven” remind us of the four pillars of Confucian wisdom, as soon as we start with the principle that the idea is rather to live in harmony with Nature, necessarily and de facto the consequences are not at all the same.

JPS: Yes, that’s absolutely true.

PART 2

JPS: I wanted to come back to this beautiful quotation from the book I mentioned earlier by Jim Harrison and Gary Snyder and so it talks about rambling… And you wanted us to talk about it Thierry: “Rambling is very valuable in terms of survival. The rambling is one of the engines of the evolution. The evolution does not function entirely on the basis of intelligent mechanisms. There’s also a good deal of extravagance at work.”

TS: Yes, that’s quite right and I like this idea of rambling very much then, it’s true that art historians have their hobby and in particular, because what I appreciate enormously the preparatory works of artists that go from the first sketch to the finished work and that allow us, in what we call genetic criticism, to see what is the evolution of the artist towards his work. And finally, we are in the middle of a rambling process that we can identify, because we have the elements. So it’s true that with you, it’s a little more complicated because there is no real preparatory work; on the other hand, we can look for the divagation when we examine all the layers one after the other, that you accumulate on your works; there, we see well that there is a divagation, similarly through time and also through space; since the sources from which you draw, it is as well in pre-Columbian Art, in Amerindian Art, as in hentai Art which is much more contemporary and Japanese, the ancient Egyptian Art also, therefore there is really a whole source of wandering I would say vertically and horizontally.

JPS: It’s true, yes, all directions, multidimensional! But to come back to what you just said, I will always remember that I went to see a Kandinsky exhibition at Beaubourg in Paris, many years ago, maybe 30 years ago and there was a big canvas and there was the little preparatory drawing next to it. And the preparatory sketch was full of life and joy but the final oil painting was completely blocked and that’s what I want to avoid in my work, really; no preparation, I don’t prepare anything. Well my images are prepared of course but I want that chance, coincidence or vital energy to circulate freely, that is very, very important, even basic, yes!

TS: Yes, it’s true, I work with contemporary artists, who tell me that the preparatory work makes them lose their spontaneity, so they prefer to work directly, which I completely understand. But moreover, often, when I examine the preparatory work of artists, from the 19th century or others, it’s true that I sometimes have a preference for the preparatory work, rather than for the final work.

JPS: Because it’s not the idea that’s there, it’s the primary energy, what drives us. It’s the soul somehow, we could talk endlessly about the disappearance of the soul today but it’s the soul that is there, yes, truly. I wanted to show you some drawings from which I drew my images. It must be said that what marked me, mainly, to make a somewhat cosmic work, is of course my trip to Egypt with my grandfather and my sister, because I was lucky enough to see Nefertari’s tomb and to enter this finite space, closed but which is also paradoxically cosmic at the same time. It is a little bit what one finds in my work, my work is finished, closed but I hope that one can reach another dimension… And it is the first function of Art to make us reach something more powerful and also beyond death, because, finally, all these tombs were decorated for the dead and were not made to be seen. In some way, we rediscover them today, after 4 to 5000 years of absence.

TS: Yes, all Egyptian art is funerary art.

JPS: Absolutely, yes. So it is this Art that marks me as well as the Art of the Maya. Here, we see for example the Bull-God Apis which brings the mummy in the other world. The power of the animal is magnificent and it is thanks to its power that we can enter the other world and today, it just ends up as a slaughter animal. So, all this marvellous and ‘magical’ relationship that we had with the living has of course disappeared, that’s really sad and so I wanted to show you this other image because we have here a painting, It’s from a book by George Catlin, a painter from the 19th century who traveled, he took his easel and he witnessed the disappearing traditions and customs of the North American Indians, of the plains, and here we see this circular assembly of skulls and there are scaffoldings too, in the back. That is to say, after people die, they let the remains dry in the air for 2 to 3 years; we often saw in the movies the people passing through these Indian cemeteries and when the skeletons have completely disappeared, they put the skulls of their ancestors, like that, in a circle and thus, it creates what we call a tribe, a community. But unfortunately today this tribe, this community is more or less lost, even with our dead within us, so that’s probably why we feel so lonely because there are not so many funeral rituals anymore and that’s what’s bothering me a bit, this disappearance of rituals.

TS: There are two aspects in the different visuals you show us. There is a first aspect which is the figure of a god or in any case, a spiritual entity; the fact of showing it and we find them in your works, they are included in your works, it is also to revive it. I was always very surprised by a fantastic novel of Jean Ray entitled Malpertuis where he makes evolve in a house some characters and one realizes, after of a certain time, that these characters are in a human envelope but that they are the gods of Olympus and they finally say: “We will exist as long as one will speak about us, the day when one will not speak any more about us, we will evaporate.” I think that’s absolutely true and that’s what we find in the works that you make; it’s that you bring these entities to life, whatever the geographical area and the century to which they belong, you bring them to life by materializing them in a certain way. And then, there is a second aspect that seems interesting to me, there, in the last visual that you showed us with this circle of skulls, it is the importance of the ritual. Rituals are not necessarily religious, they can also be quite simply social; rituals create links and they are also pillars of culture and it is true that we find rituals like this one, which is an Amerindian ritual, we find them in many other cultures… Perhaps it is something that is a little abandoned today in the West?

JPS: Well yes, we don’t have the practice anymore, we don’t practice of course! And that hurts everybody, we are not going to be backward-looking and say that it was better before, but the relation to death is one of the relations, the first one, that defined Humanity. So, of course, when we throw the dead in garbage cans as we did during the Covid pandemic, well almost, I extrapolate and exaggerate a little but I think that the position of the Man towards the bodies, the parents, the grandparents or the children who die, it is important. What one can do as artists? Not that much, but we can at least speak and testify that at certain times, these rituals once existed.

TS: There is another aspect of your work that I find quite interesting when we look at each of your Plexiglas for example, it is your appropriation of space. There is no zone where you leave a void, the whole surface is covered and I find that really fascinating because, finally, you don’t leave the gaze any opportunity to rest, the spectator has to look deeply and do a real analytical research in order to discover all the layers that you superimpose and without having, I would say, the alibi of a zone that would have remained blank.

JPS: Neutral, yes!

TS: Yes, neutral, somehow, that could allows it to rest.

JPS: Yes, you are absolutely right, yes! I work with wholeness. Yes it’s true, life is fullness of course, yes

PART 3

JPS: I would like to evoke, after many discussions with you, and after many readings on Buddhist philosophy, I wanted to emphasize this part which is entitled: “Ego exit” that is to say the exit of the ego. And I, as an artist, I really want to get out of an individual thought to enter into a thought, a collective unconscious; what we talked about earlier and I can reach out to that thanks to eroticism, to the sacred and to the omnipresence of sex, because it’s true that my work is often very sexual, as I think that sexuality, it’s of course the primary origin obviously and you, who are a specialist of the History of Art linked to sex, maybe you’d like to talk about it a little bit?

TS: Yes, all the symbols that you bring together in your works have, because they often have this very ancient origin and therefore, a relationship to Nature that was largely older than Western culture, if we consider that it begins with Greek philosophy. Finally, you have references to fertility, to the rites of fertility but also to its opposite which is the finiteness thus the relation to death. We also have references to beauty, to pleasure, to suffering, it is very complete and what is interesting, it is this intermixing, this mixing together that you practice of the sacred and the profane, it is something which is often very foreign to our current way of thinking, where we will consider that the sacred and the profane cannot mix, where we will consider that there is a hierarchy, the sacred being superior to the profane and in your works it is absolutely not what we find; you are going to superimpose the sacred to an image that is going to be of a powerful eroticism, as for example certain Japanese hentai and finally, we realize all the difficulty that the contemporary public will have to really understand your work. We saw what happened from time to time about “The Origin of the World” by Courbet. And I would say that the artist today, finally, is caught between two choices, on one side the conservatives and then on the other, all this new progressivism which, for example, I think of neo-feminism, which is no longer at all pro-sex feminism, which is a movement that has had its importance historically, but on the contrary, we arrive at a kind of anti-sex feminism that will see the evil where it is not, as long as it is a work of Art.

JPS: Yes, it is true that today, not only morality has opened up but the problem is that the market has closed since all what is sold on the Art Market are mainly politically correct works, we have often talked about that. There is also the money which takes a large part in removing a whole section of the Art nowadays which seems not having any more reason to exist. In France, if the collector François Pinault does not buy your works, your works do not exist! You cannot show it, neither in museums, nor in galleries, that poses a real problem… And well, we don’t really have the solution. It is creating a great frustration for us, today, to be an artist, even if we try to make art that works as a snowplough, that pushes, that opens the roads; and we open the roads for whom? For what? This exhibition has been presented here for two years and I have had absolutely no feedbacks, neither good nor bad. One has the impression that Art passes like that… It is not even a river. And I know that my work has strength and force and I would like that somehow the public becomes aware of it and that it tells me so… It’s true that this is a big question to ask oneself today.

TS: Yes, that’s the difficulty. We had an art that was, for a long time, religious or in any case close to certain rituals; then, we had a more decorative art and what always amused me a lot in the 19th century for example, were the art dealers who made a fortune by renting some paintings of great masters to a bourgeoisie who could not afford to buy them but who still wanted to hang on their walls a great master for a month or two in their apartment, it was very funny. And then finally, we arrive today, with the Art Market, at a notion of ‘Art investment’ and it is true, that to consider Art as an investment, that is to say to consider a work of Art as real stock market exchanging goods, I admit that I find that rather worrying.

JPS: Yes, it’s absolutely true, it’s a difficult situation, our times are a bit harsh, not only with this Covid, I think that the life of the artists has always been a bit difficult obviously, one should not complain too much. It is a beautiful life nevertheless, imagine that I have the chance to be exposed in this museum, here, that my work is presented and that people can have the chance to come to discover it. And you talk about the 19th century; what is deeply questioning me is what was this great power of the French writers and the deep attraction and interest of these French writers towards the Art and the artists, because now I am reading Stendhal’s book Rome, Naples and Florence and although he often criticizes French mentality, he says: “Our people cannot rise to understand that the ancients have never done anything to decorate, and that with them the beautiful is only the projection of the useful.” Art is useful and it’s very important to say it, it’s really very important to say it, we must not lose sight of that.

TS: It’s interesting what Stendhal says, because at exactly the same time, Théophile Gautier is going to take almost the opposite position, but to get at a rather similar idea, finally, the 19th Century, with its technology, machines, etc., is a very utilitarian century and that all the strength of Art, is precisely to be useless.

JPS: Yes, it’s true!

TS: Finally, there are two arguments that seem to oppose each other but that end up at about the same level, that is to say, putting Art in a place superior to everything else.

JPS: Yes, if it’s useless and it’s superior. Yes, you are right! I wanted to finish our interview with this sentence of Jung that I appreciate very much and I wrote a text: Uxmal-New york, a Mayan Diary as I often traveled with my friend Olga to Mexico, to Guatemala, and when I came back from Mexico and found myself again in New York, I said to myself that something had disappeared and was missing me, precisely the spirituality. And because of this high technology which allows us to travel more easily but which also handicaps us a little. So, I wrote a text about it and as an introduction to it, I added this short sentence from Jung that we should think about: “When we think about the endless growth and decay of life and civilizations, we cannot escape the impression of absolute nullity.” When you look really carefully, everything disappears, except Art, in quotes. “Yet I have never lost the sense of something that lives and endures under the eternal flow. What we see, is the flower, which passes. But the rhizome remains.” Like Art of course, it’s in Jung’s book Memories, Dreams, Reflections. And I hope that Art can perdure and also feed the unconscious of our contemporaries, it is very important.

TS: I really like this image of the flower and the rhizome. And finally it is an image that brings us back to your work, that brings us back in particular to the works on which you worked around the lotus flower or the water lily. And we have exactly… it is enough to observe any pond, we have exactly this image: every year, the flower of water lily disappears but the rhizome, which is anchored at the bottom of water, remains and every year, this water lily is reborn, thus I find there, a very interesting analogy.

JPS: Thank you Thierry. Would you like to add something?

TS: I think that, to be really aware of your Art, it is necessary to see it in person, therefore, I can only invite people to come here, to the Museum of Fine Arts and Archaeology of Besançon, to see this quite amazing exhibition. It’s a great installation that will allow you to get a better idea than with just only visuals.

JPS: Thank you again. I would like to point out that you are the co-curator of an exhibition that is currently taking place at the Courbet Museum in Ornans. “Courbet-Picasso, Revolutions!” (July 1 – October 18 2021), which is a wonderful exhibition. Thanks again to all.

TS : Thank you.

Websites: https://www.jpsergent.com | https://www.thierrysavatier.com | https://www.mbaa.besancon.fr

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/jpsergentartist | Thierry Savatier | https://www.facebook.com/MBAA.Besancon

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/jsergent

Twitter: https://twitter.com/jpsergentartist

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/jeanpierresergent | https://www.instagram.com/mbaa.besancon