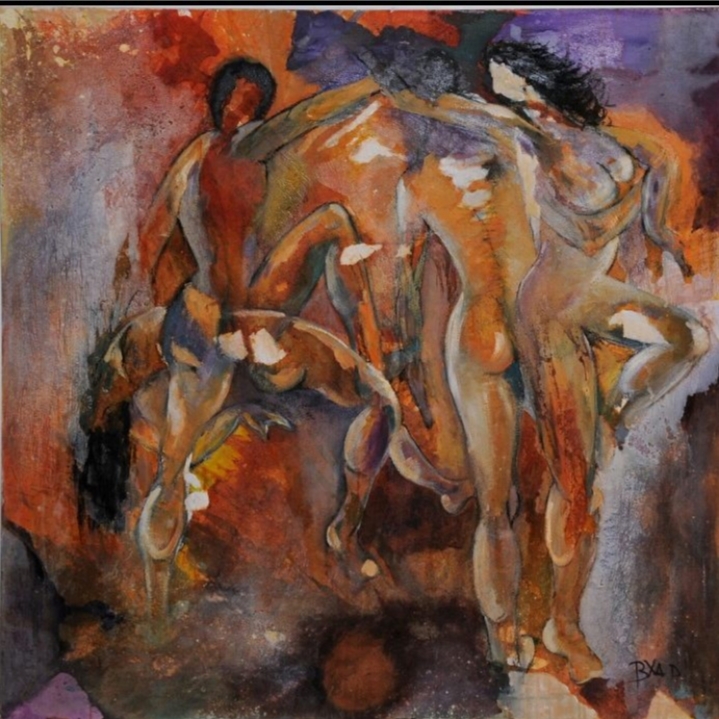

They are huddled together, their slumped bodies and extended hands passionately dramatizing desperation, their collective nightmare. These immigrants are the forgotten, souls lost in a tense, highly-pitched political battle. Some have wandered through the Sahara carrying their infants. Others have hid in transport trucks, or been smuggled onto makeshift boats only to perish in the Atlantic. All of them dreamed about starting new lives, escape, and freedom. Now they are embattled, ensnared in a “numbers’ game” and in western Europe’s increasingly-restrictive policies towards immigration. If managing to survive their hazardous flights to more tolerant Morocco, they coil in doorways, aimlessly lie at the port, or go begging in the streets. Impacted by their misery, Moroccan painter Souad Byad brings food to them, and listens to their upsetting stories. Transfixed by their cries for help, she remains in their midst, unable to say a word. She’s ultimately “pushed” toward her canvas, hoping in “some modest way,” to convey their suffering.

“Painting is a way to shed light on their problems,” says Byad, pointing to a canvas in her Casablanca studio. Satisfied one woman’s beseeching eyes mirror the pain of “an unknown future,” this former furniture/textile designer shakes her head dejectedly. “They have such desperate gazes,” she soon continues. “All too often they have been taken advantage of by smugglers. They still have a semblance of pride, even if they are hoping for a breath of fresh air.” Byad can easily identify with these immigrants. She too has dealt with hardships. Admitting “it was extremely difficult to be an independent woman in Morocco as a painter,” Byad often felt cut off from her surroundings. “I often sensed the public didn’t take me seriously.”

She still persevered. Inspired by Egon Schiele and Modigliani, yet still saying “I know myself, I have my own vision,” Byad overcame still-dominant Moroccan prejudices. That women “must remain in the kitchen.” After chuckling “I am a good cook, I make wonderful tajines,” Byad brushes aside any talk of male sexism. She instead recalls participating at the Salon d’Automne in 2014 and earning the top prize at the prestigious Salon des Beaux Arts in France for her painting Duel in 2017. A woman fights for independence and life in that tableau of anguished cries. She is trapped–and during this period Byad was also struggling. Riddled with insecurities, she wondered if it was possible to overcome male sexism, and to financially support herself? “I was very afraid of not having money, “she confesses. “I didn’t know how I could live, sell paintings…So many paths are closed in Morocco….a woman can’t always express her deepest emotions.” The “duel” finally ended. Byad’s passions triumphed.

Wedded to her oils and canvases, she felt impelled to paint “lives” in the abstract”–but to still picture the daily, unfolding scenes of angst at the Casablanca harbor. “It’s their eyes, they are so full of sadness,” rues Byad, who unleashes her welter of emotions in Oceano nox, la nuit de l’ océan, a series of ten gripping paintings. Reminiscent of the graphics that typically accompany Dante’s Purgatorio, these works are melancholic, even distressing, capturing the essence of lives cast aside, thrown into a limbo of hellish realities. But Byad’s paintings still manage to transcend the present, “the humiliation, the fear, the barrenness of lives strewn into a dark ocean.” They are so potent, so communicative, we establish a connection with a certain faith and stubbornness, the immigrants’ will to survive.

“I wanted to give these people a voice…to show their pride, and longing to be elsewhere,” reflects Byad her voice faltering at times. “I have wondered so often how hard it must be to embark with women and children on such an adventure. To did better than a bitter life. To have a grave…some privacy at last. I am so struck by this I have to paint. It consoles me.” Only to a limited extent. Byad walks around her studio, clearly impacted by the Dantesque woe she has revealed. The images seem to leap off the canvas. They speak; the question is, are we listening? How many more immigrants must languish in Morocco or die making their way to Europe? “These paintings allow me to release buried emotions, and that gives me glimmers of hope,” says Byad. “Like stars that appear when the sun goes down…All these beings that coil, mix, hands asking for help…Their tears usually flow in silence…but I hope not here. Maybe my paintings will allow their crying to be heard.”

Written by Edward Kiersh