Clinging to hope, the defiant belief Paradise can be found, the intrepid Finder of Lost Souls treks through the rugged Mexican wilds. Toting her cameras, she skirts a perilous ravine edging the mountainous Cerro de Chipinque. It is late afternoon, and despite the heat, she presses ahead, ignoring the sounds of animals scuttling through the woods. “Come on, we are almost there, stop arguing so much, and let’s go,” urges photographer/videographer Elisa Guerra, 34, softly encouraging two companions, Clara and Martin, to quicken their pace. Intent on filming compelling stories, those that promise “reflections, genius, transformative emotions,” she sensitively understands that this journey outside Monterrey is a risky one. Clara is manic depressive, Martin schizophrenic. But always believing in “possibilities,enlightenment, and change,” she confidently expects her often startling photography to initiate “revelations and new beginnings.”

Guerra has taken many of these emotional, often heart-wrenching odysseys. Hoping to “mine gems,” to explore the soul’s deepest subterranean recesses, she lifts masks and navigates the conflicted. Her photographic world of “witch girls seeking demonic powers,” prostitutes, and voluptuous women awakening from “amnesia,” centers on “love constructions,” “overthrowing bondage and liberation.” It’s a daunting world, often with photographic tricks and mysteries. Guerra is serious, reflexive, and also the trickster.

Believing photography is a deeply collaborative effort, a mirror of her own revelations and a connected series of “awakenings”–a “biblical” story–Guerra is no mere observer, simply using a cellphone and a Nikon d5300 to capture the tension and suspense in people’s lives. She is a conjurer of desires, often emotionally involved, cathartically. “The camera is only the means to show what are the depths of each person,” explains this award-winning photographer who has been invited to this year”s Florence Biennale for contemporary art, and to the Hong Art Museum Chongqing. “Yet at the same time it is also a reflection and liberation of my being.”

Mirroring the characters and their quests in her storytelling images, Guerra is also “on the road,” looking to find her true destination–”to feel, to connect” with true inspiration. “Hurry, you can see the building now, come, let’s have fun, let’s see what happens,” implores Guerra, consistently met with indifference. “Let’s hear the color of what no one sees.” They push ahead, approaching the decayed ruins of an estate once owned by a Mexican general. His Xanadu, dominating a plateau 1270 meters above sea level, this former summer home with steel-barred windows and cracked stone walls will be the backdrop for Guerra’s filming the distressed, often bewildered couple.

Hoping their “taste of freedom” in this setting will be therapeutic, that her cameras are less a machine and more “a flash of light” able to heal, Guerra insists, “People can overcome…(create) a love story with a touch of mystery plunging into the depths of madness, combining emotions so that they learn to feel what the other feels…establish a reflection that calms that madness…(initiates) a little normal.” Here there is no normality. Only distortions, distractions, and as Guerra says, “masks, pieces of poison.” The couple’s shifting moods and fantasies are so troubling, they are given straitjackets. What will happen next?

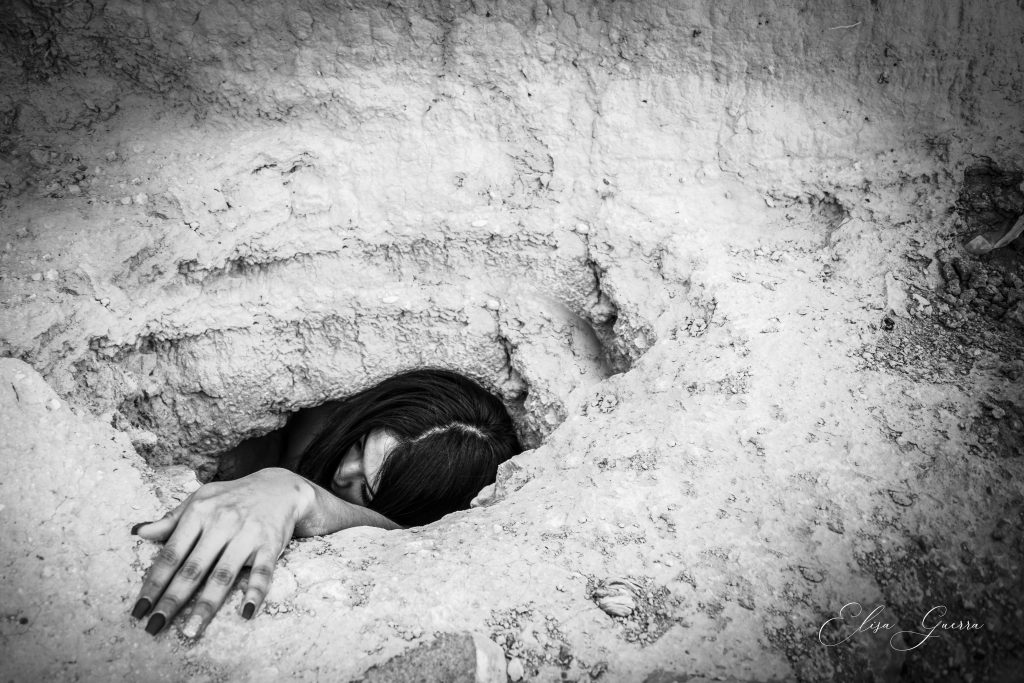

Surprise, a cinematic suspense, are hallmarks of Guerra photography. In her Sleep Tight series, a white-gowned woman lies prostrate on a grave, her own destiny a question mark. What happens next to a naked seductress standing next to a horse in the sea? A buried woman reaches out from a ditch, will she escape her interment and find freedom? Migrants in flight, escapees of white slavery–uplifting the desperate is Guerra’s passion. Her raison d’etre. “Let’s take photographs, laugh, come,” she implores the couple. Ignoring her, they scoot in and out of rooms, shrieking at each other. Playing a distorted hide-n-seek game, vacant-eyed Clara squeezes herself into a tiny alcove, huddled in the shadows. A distraught Martin clings to walls.

They suddenly move out of their respective hiding places, and link hands before jumping onto a wall. It’s a brick slab looming about 60 feet above a stone terrace outside the house. Their hands locked, they move precariously close to the edge of the slab. They are poised to jump…Invisible, numb and frightened, she is reduced to squeezing into a refrigerator. Iciness has been her life, the faceless abuse of being kidnapped and thrown into white slavery. “Anna doesn’t know if she wants to return to the ‘safety’ of slavery, or to think about her being robbed of a childhood,” explains Guerra, the daughter of a men’s nightclub manager. She has known many “broken women,” including Laura and Sofia, who gave her a beautifully-colored record album which propelled her interest in “painting stories.”

Never content now with simply choreographing poses, or the mere transitory moment in time, she’s consistently seeking the transcendent, constructing provocative images that give the abandoned visibility–in comprehensive series of images, chronicles that navigate arduous emotional passages. “Anna is clearly in great distress, decay,” sighs Guerra, who first started taking photographs with a camera four years ago (“it was thrilling, living with horses, taking pictures”). “But Anna wants to live…discover…much of my work is about overthrowing mental slavery…finding a new life. Now Anna might go to America, she has a mission. “Turbulence abounds in this White Heat series: drugs, child prostitution, and the physical abuse of “lost” women. But the series is also about “transitions” and hope.

In the equally-provocative series Traviata, a photo of a voluptuous, scantily-clad woman lies suggestively next to a tree, allowing us to wonder if she’s still a prisoner of her abusers, or if she is thinking about a more rapturous future. Can she escape the fate of another desperate White Heat victim? Mirroring the deepest depths of dehumanization, a young woman is pictured groveling in a hole. Explosively, it captures horrific trauma, the deepest depths of dehumanization. She seems to be trapped, yet her hand is emerging, bravely reaching…will it be life or death? “Life is terrible suspense,” rues Guerra, “especially for brutalized women. Some are prostitutes, others are housewives, others sell chickens. They have all gone through torture…This woman, lying alongside the tree, there she can remember her roots…her essence. She can think of that and move on. Desire to live free.”

A Fellini-esque, risk-taking leap into a graveyard where dreams collide with reality. That’s Ictus, Guerra’s bold, provocative picturing of love and upheaval. A surreal visit with ghosts, a desperate woman in a white wedding dress lies prostrate on a gravestone. Death has cheated her. On the eve of their wedding, her beloved died suddenly, and now she will continue to look for him, searching for a miracle–or edging towards insanity. “Fear and desire…’til death do us part…truncated love…a bit of madness,” says Guerra, delving into that “very thin gradient” between enlightenment and the inexplicable. An admitted believer in love’s “redemptive powers,” she often returns to such themes as abandonment, the demonic, memory and safety.

In Santa, a clash between an indignant Satan and God, sinful LIlith is “martyred,” the victim of their eternal battle. A long-haired beauty, she too is in a graveyard, naked, kneeling next to a giant Cross, waiting for forgiveness, “falling shamelessly …nailing the fangs and leaving scars like the memory of her passion. ”Lilith lives with pain, doubts, the anguish of not knowing her faith. So does The Little Mermaid. Erotically pictured on a beach, and in the sea standing next to a horse, this shapely woman is similarly waiting, wrestling with conflicts, hoping to flee from a world teeming with “bad friends.” Allowing the sea to wash over her sensuous body (as if it would spiritually transform her) she sits provocatively in a chair, exposed, defiantly proud of her nakedness.

“This prostitute works as a dancer in a nightclub for men and wants to change her life,” says Guerra, reverentially, “The beach is a perfect place to recap, to enjoy the beauty of life. She feels free, presenting herself to the horse, stripping her soul…the horse accepts her no matter what she is…dedicated since he sees her essence, without prejudice like people.” Herself the victim of “being misunderstood throughout (her) life…of false perceptions…doing crazy things for love,” Guerra suggests “the camera protects me,” prevents her “depths” from becoming visible. Yet there are still shades of visibility. She enjoys “playing games” with time, space, and matter–at times turning secretive, at others, everything is a “double exposure”–her images becoming self-confessions, intensely revealing her own personal tribulations and those of her fellow messengers.

Finally, after weeks of conversations, another piece of her “mask” is lifted. One more protective veil taken off. Speaking about the M31 (or Andromeda) series, which stunningly depicts an immigrant mother’s “ struggles, strength, triumphs, and rewards from fighting for her children,” she confesses, “We all (face) dangers that have to be crossed…We all go through obstacles, struggles, mistakes… Self-taught (photographically), I made many mistakes. Many. But I learned to face fear…to travel within…and show it through my camera.”Escaping reality to enter a foreign multiverse, to gain millions of perspectives, Bella suffers madness to understand love. She is the constant adventurer, the constant victim of her own passions. In Uncooked, loves whispers, lightning pierces, and all recognition becomes cloudy. It is a common malady, a splintered heart. All the glimmering jewels, tight-fitting dresses, and sexual enticements are not enough. She is shipwrecked. Charleston is glamorous, a coveted prize in this nightclub of prostituted dreams. Men abound. An object of great desire, she is still alone, searching, wandering, enduring one shipwreck after another.

In Welcome partnership is eternal bliss, offering an orgy for the senses–especially when those bonds are between two demons in the search for souls. They offer their victims love, infinite pleasures.But do they? Typically in Guerra’s phantasmagoric world, a universe of zombies, apparitions, and magical sprites, love is a spectre–fleeting and also a blank check for hurt. She-demons never show mercy. Certainly not this one. She searches for a mate, goes through Hell to find one. Many vanquished souls later, she finally finds the Chosen One, and guided by Guerra’s boundless imagination, the loving couple set off together, lust and indolence awaiting them. Guerra’s ties that bind and unravel–the corruptions and madness that take the love-stricken to arid, frightening prisons, to solitude, and moments of redemptive delirium. Her imaginarium is an ever-expanding constellation, a multidimensional parade of broken mirrors, acrobatic flights of fantasies, and plunges into the depths of emotional tsunamis. A “painter of life,” Guerra fearlessly navigates the unconscious, paradoxical juxtapositions, guilts, infinite progressions and regressions, relentlessly in search of the true miracle, love. Her camera goes everywhere. But that too spells upheaval. The Finder of Lost Souls also gets lost. She must find deliverance.

Falling in love amid the smoke and fiery ruins of unrequited love is one more trip to darkness, to the strait jackets worn by the desolate and infirmed. These lost souls wait. They suffer. Guerra’s refugees need to be rescued, inspired by her Nikon, and led to the Tea Party where slavery ends, masks are lifted, and madness in the name of love is understood, caressed, and allowed to flourish. But how can Guerra provide such hope if she too is confronted by doubts and demons? A strong believer in the eternal–in her own heart and ability to inject feelings in her photographs–she feels her “essence”–spreading a certain gospel–will lead Charleston, Bella and the others to the Promised Land. That is, of course, if she returns to the origins of life, the innocence of childhood in Wonderland, and finds Alice. Guerra’s already found countless “Mad Hatters” spinning too many false illusions, and walked through enough graveyards of lost dreams. Having delicately straddled the fine line between madness and the “genius of true love,” she must only recognize one remaining truth. That recognition becomes clear in the final image of her stunningly-colored Alice in Wonderland series. Warmly greeted by Lewis Carroll, the White Rabbit, the Cheshire Cat, and the Queen of Hearts, Guerra is inspired, strengthened to continue her mission Now all becomes clear. She is Alice.

instagram @elisa_guerra

Written By Edward Kiersh