Before escaping to Barcelona, Istanbul’s Blue Mosque, and the Acropolis, the 13-year-old was bullied daily by rock-throwing schoolmates. She tried to find refuge in her art books, and fantasies. But as she recalls, life in the icy oil fields of the Taiga was barren, “a soulless wasteland. ”Dodging stones, and surrounded by a deadening landscape of oil rigs and “trees like skeletons,” the precocious teenager found a way to flee.Through her drawings and boundless imagination. Both led to a boat in Odessa, then on to Gaudi, the Parthenon, and the ruins in Pompei. Those sights and their Nikon moments, left a lasting impression. So did the feeling that she could be the habitual Navigator, fearlessly venturing into the unknown. Now Irina Grechiuhina travels through sealed mirrored chambers, infinite intersections of reality and abstractions, and paradoxical illusions. Nothing deters her, no games of chance, no bewildering kaleidoscopes of memory, and conventional constraints.

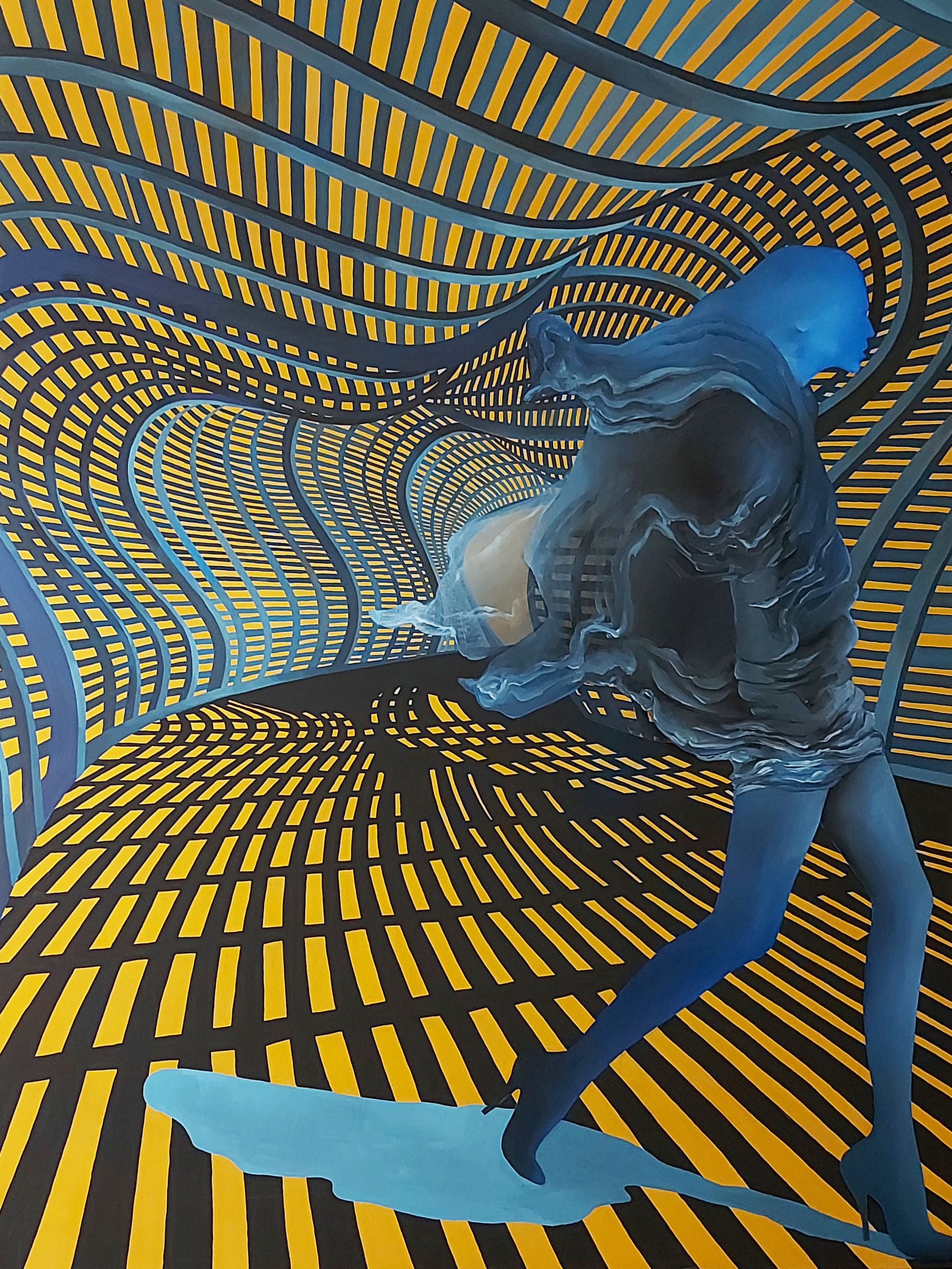

In adventurous architectural “geometrics and ornaments,” or in paintings like Futurological Congress, she simply pushes ahead. She howls, in fact, questioning “the natural order of appearances.” Typically defiant and inventive, Grechiuhina is poised to open those “secret drawers of the mind” Salvador Dali penetrated, and to invert Time and Space. Her rebelliousness is not new. It erupted in Odessa–the moment she stepped aboard the Taras Shenchenko cruise ship. Suddenly free of her tormentors at school, and the depressing oil fields, she sat atop the five-deck ship, chain smoking menthol cigarettes.

“I was reborn, it was culture shock…I was free,” laughs the tall, long-haired Grechiuhina, who was awarded that two-week “cultural” cruise after winning a nationwide Russian drawing contest.“I sat on the deck those first nights, smoking, being so ‘wild,’ and amazed that I was there. Seeing stars so far from my hometown (Pyt-yakh), and my mother… I was carefree…I came home a different person. ”In the Taiga life droned on, just a claustrophobic unhappiness of daily skirmishes and predictable dinner table talk about the unrelenting chill. She continued to draw, imagining, laying down abstract guideposts for future, far-flung wanderings.

Her questioning the Sacred, an aesthetic that allows her to travel unfettered into inventiveness, was taking shape. Yet it couldn’t flourish, not in the Taiga.“I was so alone, so unhappy,” sighs Grechiuhina. “There was nothing…my friend drowned in the swamp near me.”That was before her awakening. Her finding Gaudi.“His chaos and beauty knocked me down, a genius…he experimented, dared to cross boundaries,” she marvels with a certain clarity. “I recently returned to Barcelona, I remembered what Gaudi meant to me. What I saw in Pompei, in Greece. I found so many surprises.”

Now we are the ones finding the unexpected. Still impelled to upend the immutable, to shape new puzzles and optical illusions, Grechiuhina, 39, delves deep into the Digital Underground. Here she communes with memories, double images, and fanciful confusions. Constantly probing in this disturbing work, she wields a scalpel, shedding light on her autobiographical terrain. “Everything was so strange when I came home,” she says after taking a phone call in her Moldova office. The founder of an architectural firm, she is talking with a prospective client, a Romanian restaurant owner.Now Grechiuhina is known internationally for her restaurants which “retell old fairy tales in a modern way,” clubs, and apartment complexes. In Pyt-yakh, she was seemingly in Siberia, quarreling with teachers, steering clear of gray wolves and caribou, and always learning to be resilient. Relying on help from her grandfather, a Soviet Union submarine officer, she fled to Chisinau to attend school. It was a daring move, much like the silhouetted presence ascending a narrow staircase in Loosen Line of Reality. She outgrew her fears, used her long sensuous legs to “move beyond the ephemeral,” and ignored spills and conventions until reaching rarified air.

Thwarting Grechiuhina’s climb, Pavel died. Her grandfather (“a poor soul”) is described as “my strength, my calm, I still remember him whistling in the garden. He was everything to me.”He inspired her to enroll in the Academy of Music, Theatre and Fine Arts in Chisinau. Insisting “I was the school’s best student,” she whimsically hoped to fulfill exam requirements by printing a set of Japanese gravures. Her instructor was not impressed. They argued, and Grechiuhina ultimately left school a few months before graduating. “I was offended, she refused to show these engravings in the exam. So I forgot art. I only became interested in architecture.”She subsequently went to the Moldova Technical University, and in her third year was invited to work in the Moldovan bureau of a Moscow company that was designing buildings for the Sochi Olympics. But Grechiuhina remained the iconoclast, the inveterate questioner of norms (who avidly read Carlos Castaneda and enjoys the films of Andrei Tarkovsky). By brashly leaving the Academy, and demanding creative freedom at the bureau, she clearly broke the Moldovan mold of the acquiescent female.

Her independent thinking was a prefiguring of two enigmatic presences in future paintings, XYOO and Lusy in the Sky. Two weightless defiers of life’s chaos, they reflect Grechiuhina’s demand to escape “vacuous trappings and superficialities”–to find existential meaning. These airborne caprices decipher parables, turn an elephant into a muse, and avoid seductive lotus flowers. All to solve one mystery: Who Am I? Grappling with ambiguities, Grechiuhina relished the prospect of opening an architectural firm by herself–yet worried this “step into the unknown” would plunge her into overwhelming debt. “I wondered what to do for a very long time…I just didn’t think I could do it without forming a partnership,” she laments. “Freedom always has a high price.”She took the risk. Renting a “prestigious” space in Chisinau,Grechiuhina founded Zen Design (2007), and was soon styling Andy’s pizzerias. Those early efforts were so successful, she’s designed 50 restaurants for the chain. Zen Design now boasts 12 architects, a few freelance designers, and a large support staff. It’s become Grechiuhina’s ever-demanding “spiral” of meeting with prospective clients, turning their artistic visions into practical solutions, and massaging their egos.

Eager to style welcoming, luminous habitats, like the fertile refuge enriching her Galapagos sea-dweller, she explains, “architecture is playing chess, my spiral of puzzle solving..restaurants always involve a game, a riddle. It’s like magic…you usually enter an old, abandoned space, and then with technology, ergonomics…you conduct a transformation. I create a new life. ”Predictably refusing to be categorized, Grechiuhina refers to Fuior, an upscale eatery in Chisinau, which features vases resembling ancient vessels for wine, mirrors made from imitation sheep’s wool, and geometric mosaics on the ceiling. Grechiuhina says the design is a “tribute” to Molodovan culture, insisting, “It’s boring to just do one architectural style. I like to float between worlds. It’s far more interesting to combine contemporary, modern with classical. I don’t like purity.”Architecture is another canvas, an expansive one which prompts her to insist, “Nothing is true, everything is allowed.” Remembering one Academy student who used goat feces as “a material of creativity,” Grechiuhina adventurously collaborates with fashion designers, landscape designers, sculptors and broomstick makers.

Proud of that collective effort, she boasts, “We are pursuing “intelligent, imaginative uniqueness.” Emphasizing this commitment, her designs are a constellation of ornate chandeliers, monkeys swinging on poles, plush velvety banquettes, and curated woods combined with Japanese pop art murals.The winner of international competitions, she has spun her surprises in China and Japan. But architecture is also a confounding sphere, complicated by budgetary constraints, deadlines, and intense competition for contracts. She still bemoans losing a lucrative hotel project a few years ago, and further complicating her woes, the Pandemic has further shrunk opportunities in the travel industry. Even before Covid-19, her freedom has been restricted. The mother of three young children, and at the helm of a respectable-sized firm (along with partner Alina Moroz), she scrambles to find time for painting. “Finding balance, what’s that?” she volunteers, “It’s impossible!” “I’m like sand in the water,” she adds, acerbically. “I think I have many lives, so many different realities. They appear, they disappear…I can’t make sense of them…I just keep moving, escaping, going from one world to another.”

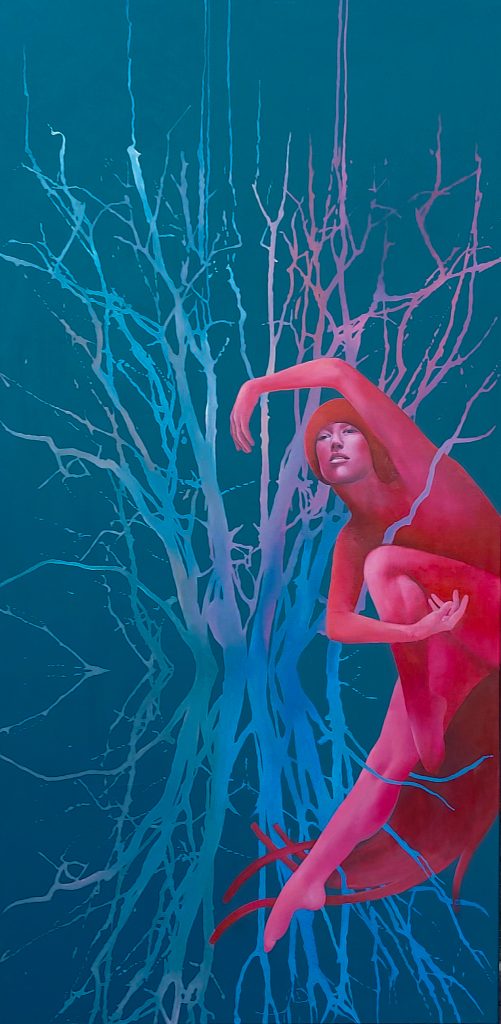

She also bolts from automobiles (The Orbital Station), submerges, and leaps into unchartered terrains like one of her favorite writers, “the mind-bending” futurist Stanislaw Lem. He fictionalized a kaleidoscopic array of speculative eccentricities (machines, dragons, cybernetic enemies) and Grechiuhina is similarly subversive. She penetrates bizarre anomalies, far-flung galaxies, and “Ministries of Secrets.”the Song of the Creator she probes spiritual enlightenment only to tangle with scowling centurions guarding the vault of eternal truths. Denied entrance, she stands firm, immutably poised to overcome barriers.Locked in a Venetian palazzo, a claustrophobic room barring illumination, the dejected sightseer in La Grande Venezia is marginalized as a shadowy captive. Will she escape confusion, be imaginative enough to find clarity? Her lusty women in Unity in Diversity feast on that “heavenly state of grace.” Even if it means flirting with heresy– eroticism in the face of Mary Magdalene–these “First Supper” card players are empowered, free to declare a new Holy Order. Part of a rising sisterhood, they are co-conspirators, provocateurs like the club-wielding woman in the Conspiracy. Fragmented, exiled, and “tired of dead-end delusions,” she wants to realize her full potential. As Grechiuhina explains, “she’s poised for action, ready to smash all closed doors.”

All these women offer clues, insights into Grechiuhina’s evolutionary struggle to reach understanding–her wading through tangled irrelevancies to embrace the inspirational. The Seductress, her latest work, pictures another transformational move forward. Resembling a legendary Amazon warrior, this purple, muscle-toned figure grasps a towering, mysterious plant. Bonding with nature, she erotically suggests, “I am a modern-day Eve!” Grechiuhina has been searching for Truth–what Kandinsky likened to a “Garden of Love”–and in a fitting coda to these metaphysical journeys, a wrinkled old woman steps into the picture. She is wise, a sage in sneakers, able to outrun the wind in Drafting Shadows Leaving Habana. A survivor of countless “revolutions,” she knows how to negotiate spirals, to be “rebellious and free.” Leaving and Arriving–completing the circle–that’s the totality Grechiuhina has been seeking. As indicated by her Cuban alter ego, it’s been an exhausting search. But Grechiuhina, just possibly, has found her Eden. Walking on her recently-purchased tract of land outside Chisinau on the Reut River, she extols, “here I feel relaxed, I am finally with Nature. “Just look at all these flowers….how special…”Grechiuhina surveys the surrounding hillsides, talks about building a small house, then quickly adds, “I want to feel comfortable…it’ll just be a small wooden house. I need this place to recharge. Now I am living too many lives simultaneously. It’s too much. I don’t know how I survive. But here I will paint, see the wild, the future.” Contentment. It is one more spiral. One more orb for her to visit, and to picture.

Written By Edward Kiersh

https://www.linkedin.com/in/irina-greciuhina-253a00189/