There they were, en plein air, a nude woman sitting with two men on the grass in a French park. Sacré bleu! Only used to seeing art depicting historical or mythological scenes, the French public was immediately outraged by Édouard Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass in 1863. So were members of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, the ruling art establishment. They were shocked by the saturation of light in the painting, the freer, brighter, intense use of mixed color, or synthetic pigments, and above all, by Manet’s blurring of reality with his own impressions. To these critics, Manet and his departing from reality was revolutionary, a bold attack on Art itself. It was!

Branded Bohemians, and later the Salon des Refusés in 1867, Manet, Cézanne, Monet, Renoir and others, were not going to be deterred by attacks from the status quo-minded traditionalists. Believing reality did not have to be faithfully reproduced–that interpretations or impressions of transient moments, erotic encounters, real life instead of carefully-staged still-lifes in a studio–these rebellious free thinkers upended the Art world.

Shrugging off all criticism, they substituted their subjective use of light and shadow for mundane realism, and depicted sensations–or what they thought and felt.The beginning of modern art, or what we can view as the underpinnings of avant-garde, they portrayed cafe life, domestic intimacy, and as exemplified by Edgar Degas in his fascination with ballerinas, singers, French entertainment in general, and with laundresses. As Degas said, “A painting requires a little mystery, some vagueness, some fantasy. When you always make your meaning perfectly plain you end up boring people.”

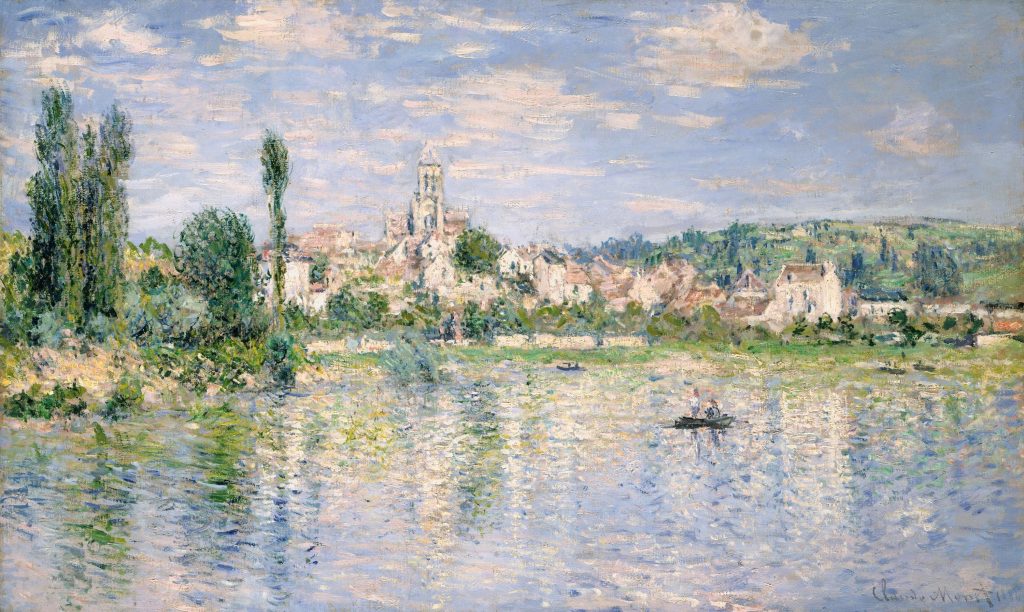

These Impressionists and their stimulating the imagination through paintings of cafe life, cabarets, trysts, and “dreamscapes” like Claude Monet’s Water Lilies, eventually won the support of Emperor Napoleon III. Seizing on the dynamic quality of the art, its independent spirit, the public also began to view Impressionnisme favorably. There was a defiance here, a boldness, and a spontaneity that was in-synch with scientific discoveries that were also transforming life–leading to new perceptions about Nature and human existence.

As Monet emphasized in his Water Lilies series, life was meant to be ablaze with sensations, an openness to illumination, and to adventurous experiences. As he wrote, “Since the appearance of impressionism, the official salons, which used to be brown, have become blue, green and red…But peppermint or chocolate, they are still confections.”His fellow rebels, coveted icons for art collectors, left us with more than museum pieces. They broke boundaries, infused painting with renewed, far greater energy–and their exuberance led to revolutionary departures in music (preludes, arabesques), literature (Charles Baudelaire, D.H. Lawrence, Virginia Woolf), and in cinema.

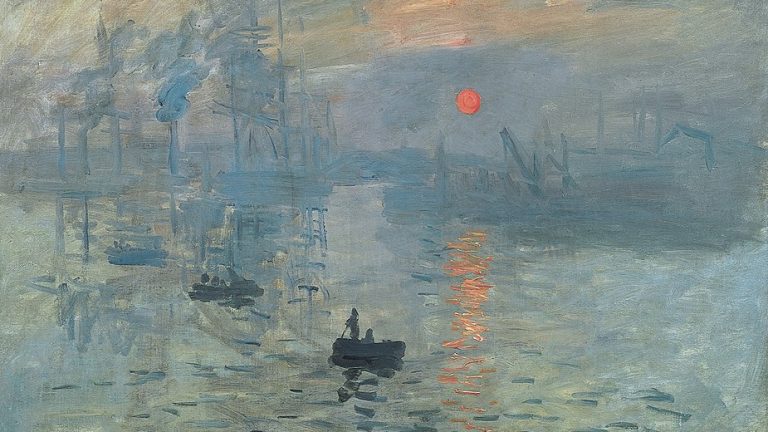

But why should we revere Manet, Pissarro, and Cézanne? They were fearless, loyal to their life-enhancing loose brush strokes and to unfettered colors. Their forcefulness and exploratory spirit set a benchmark–an example that continues to impel artists today–an unyielding craving for freedom, a defiant will to create.April 15, 1874 in Paris was born a new artistic movement at the end of an exhibition bringing together a group of painters such as: Monet, Renoir, Degas and Cézanne to name a few and which will bear the name of “Impressionism” Following the mockery of the art critic Louis Leroy invited on this solemn occasion, who ironically on the title of Claude Monet’s work of art “Impression,

soleil levant” will give the term “Impressionism” immediately resumed by the founders of the style.

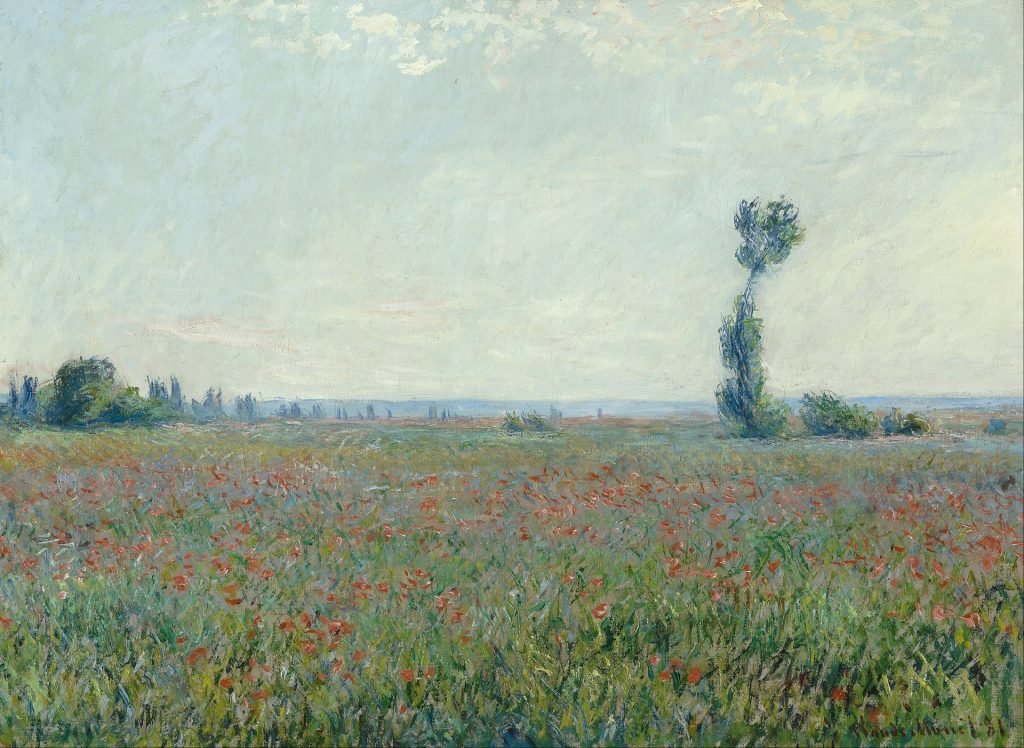

“Impressionism”: a pictorial movement mainly characterized by small-format paintings and visible brushstrokes, marked the break between modern art and academic painting which was very popular during this period.The impressionist artists abandon their dark workshops in favor of daylight in the open air, in the midst of nature, placing their easels at the seaside in Normandy, or on the sidewalks of Paris. A real artistic revolution will emerge from this collegial set of painters, who will prefer to paint everyday life with its own light effect and devote themselves to dense contrasts, rather than repeating the traditional methods of shadows in gradations. By painting the chromatic variations of sunlight, the painters of this movement will bring to their works of art an “impression” of an immediate reality, taken from life.

© Patrick QUENUM (All rights reserved)