He is queer. A quirky anomaly, wrapped in a skin-tight plastic bag, his “foreignness” confuses us. Who is this weird figure, and why is he suspended in nothingness? He is the Restless Man. A Him enveloped in a bubble of loneliness, desperately trying to protect his individuality against oppressive conformity. Appearing in an abandoned factory, faceless on a beach, or poised precariously on a cliff, Yanne Kintgen’s Him is a mere object, anonymous and ephemeral. In her videos and photographs, he intriguingly floats from one barren landscape to another. Hoping to find meaning, to “fit in,” he struggles to shed his disguise, futilely.

He remains the outsider, the queer, who allows Kintgen to escort us into a realm of lost identities, labyrinths and blurry, enigmatic uncertainties. A photographer, painter, and sculptor, she has questioned her own relevance, felt isolated. Seeking a creative metamorphosis that dissipates those feelings of “suspension…being in between,” she follows Him, giving voice to our existential wandering.

“Man perplexed by impermanence, falsehoods, standing apart from the crowd, the rebel who demands meaning, that has been my work,” insists Kintgen, eager to discuss delicately-embroidered drawings and a series of video sculptures inspired by the “notion of floating.”Sitting in her atelier outside Paris, recalling the “catharsis” that prompted her to attend Versailles’ École Des Beaux-Arts in 2016, Kintgen continues, “I had grown stale, bored. I needed to refresh my imagination. Like my character in plastic, I felt an ‘intranquility’, a lack of belonging.”

At Beaux-Arts she became familiar with new visual technologies, how to “ simulate thinking,” and admits, “I became less intellectual, freer. My years there were my fountain of youth.”“In my early work you find solitude, questioning, an attempt to penetrate meanings,” she says, looking at Chacun Chez Soi, a sculpture depicting man encased in a tiny box. “There is a fear about conforming. My father was a dissident, a socialist. He probed, feared the loss of individuality, and was always at odds with society.”

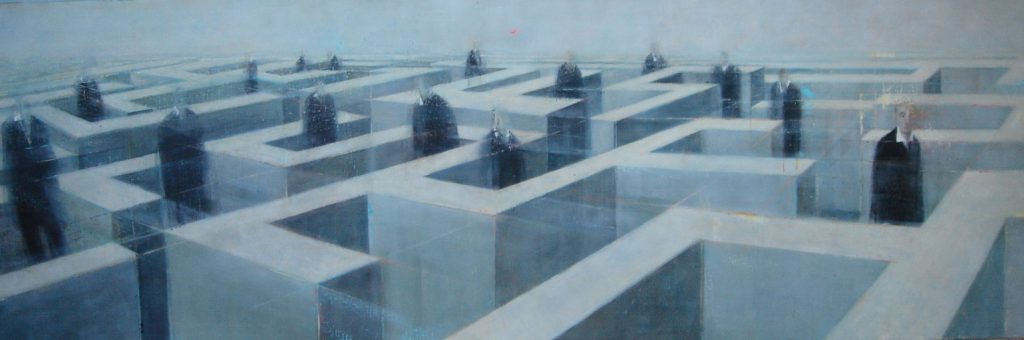

Elements of that militance suffuse Kintgen’s early paintings. Crepuscule is cheerless, indistinct figures evoking mass conformity. Fruit du Temps pictures men trapped in a “rat race.” In Labyrinthe II, one man hopes to rise above deadening uniformity. Equally melancholic, Lui is Man poignantly lost in a crowd.Able to float, “Him” is unbound. Still searching for direction, a purposeful connectedness with others, he is free to wander. All the while stirring our imagination, allowing us to wonder if he will ultimately “blend in,” and at what cost?“Before finding completeness, he’s in a cocoon of unreality…the bag is a moment…the butterfly in chrysalis,” says Kintgen, chuckling. “Every ten years I feel incomplete, I need something new. At Beaux-Arts (for three years) I became more willing to be experimental, mixed photography with video.

“Videography is sculpturing, it’s a kind of theatre offering surprises. Look at Marina Abramovic, she’s so strong, so provocative…I think my man in the bag is also a surprise, open to many interpretations. He’s passing through moments. He is alone, insecure, a message of doubt. It’s like I am looking at reflections of mirrors…probing the Invisible.”Ironically, in a world dominated by dull dystopian homogeneity, his being opaque gives him a distinct potency. Raising questions about existence, he provokes thoughts, stirs confounding mysteries.

Does Kintgen truly want her Quixotic character to “fit in”? Isn’t he more resonant as the Outsider, the unseen provocateur who can sound alarms about injustice without fearing reprisal? Adopting her own guise of invisibility, Kintgen typically retreats to her parents’ 16th Century stone house outside St. Malo, France. Here she reflects, models with clay. Insisting Brittany is “authentic, very real” (emblematic of that metaphysical wholeness “Him” is seeking), she says, “My garden is so relaxing… I love Bretonne dancing. I am a great dancer.”

Feeling freer in Brittany, Kintgen remains the “social critic” in her bronzes, but balances that “weighty” messaging with sardonic humor. Mocking our reliance on IPhones and networks in Pensees, such sculptures as Idee haut, Exchange Brouillamineux and Boite a brut, all feature skeletal, Giacometti-like figures. Tangled wires protrude from their heads, as they vainly try to communicate with one another. Echoing the obstacles, Him faces when relating to others, a man unable to connect with a woman is trapped in Labyrinthe, a helpless victim caught in limitless dead-ends. Always elusive, truth is distorted in Frise clair obscur. Here reality is blurred, as a progression of bronze heads move through light and darkness, wisdom and blindness.

Motion invigorates much of Kintgen’s work. She has fun with the oval-shaped Colibuto, a “child’s top” that mirrors our swinging back and forth before finding “the right direction.” In her world, movement means defiance, the fight against uniformity. In Le curieux, one figure boldly rebels, separating himself from a line of spectres. He stands alone, free.“This guy, he demands liberty, he’s so much stronger than the others,” says Kintgen, whose “Solitary Man” fascination has been strongly influenced by the writings of Fernando Pessoa, the Portuguese poet best known for his The Book of Disquiet. “I too can be grave, up and down. Life is confusing, disturbing.” Knitgen can find peace shell fishing in Brittany. But she is the antagoniste, with a legacy to uphold.

“Like my father, I need to go in my own direction…to doubt, question,” says Kintgen. “Passoa felt this uneasiness. I try to capture this in Him, voice my melancholy.”Asked if she would like to have lunch with Passoa, another writer or an iconic sculptor, Kintgen responds, “Rodin, I love his erotic stuff. He made one famous sculpture with three women (Les Trois Faunesses), and so did his lover, Camille Claudel. I made one too (Les Causeurs.”Growing agitated, she quickly adds, “Claudel was his model…he saw one of her bronzes, my god…how terrible (Rodin was so angry, he reportedly tried to discredit her work). I would ask him why he made her suffer. He abused her. She went crazy.”Her having lunch with Rodin? That would be quite a lively affair!

Written By Edward Kiersh