At the risk of being discovered, humiliated in front of his classmates, whipped with tree branches, have his ears forcefully pulled, the young Zulu boy continued to sketch. During math class. Or at lunchtime when other boys played futbol, frolicked with girls. Whenever it seemed no one was watching, he would ignore all his village people’s warnings–that art was Satanic, pure “devil worship–and draw. “I was supposed to only think about taking care of livestock, being a good farmer,” rues Ntuli Ndabuko, recalling his youth in Kwa Zulu Natal (or Nkandia), a village about 500 km from Johannesburg, South Africa.

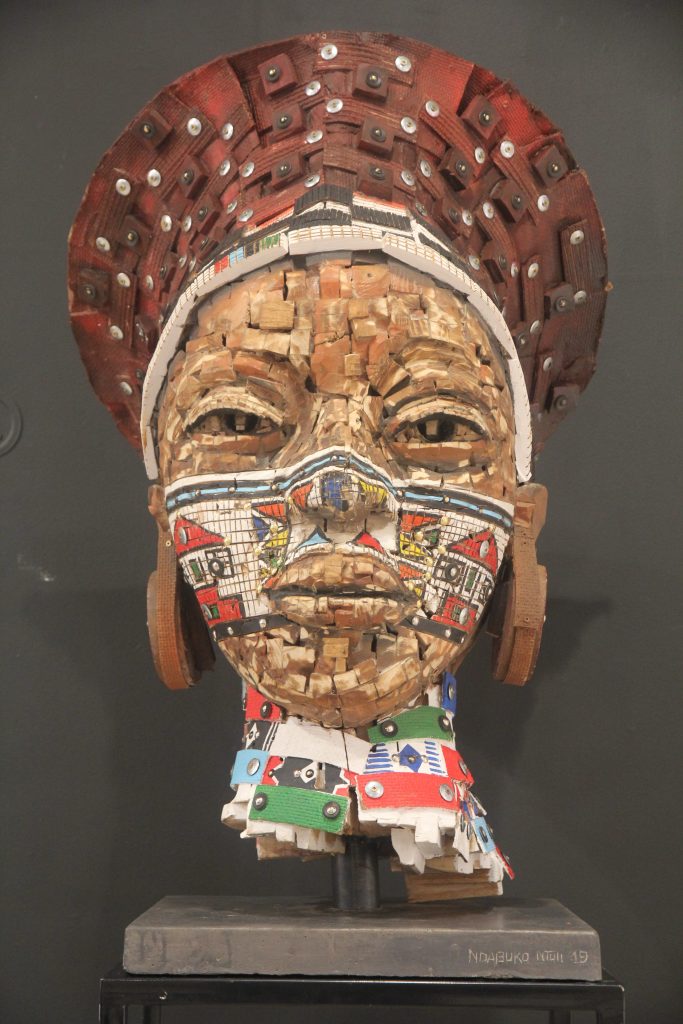

“Before doing my homework, I had to create something,” adds Ndabuko, soberly. “Our mountains, our attire, the animals in the kraal (a traditional village). There was so much life, I had to pick up clay or a pencil. Creating stories about the Nguni (his cultural roots)…It’s the only way to keep them alive.” Now Ndabuko, a Maskandi musician, a traditional healer and a sculptor of bones, car tires, and bottle caps is still inspired by his Zulu ancestors. Reanimating their illustrious past with flamboyant and mysterious nuances, this Sangoma ritualist sculpts revelatory “presences”– intricately-detailed, pine wood likenesses of Zulu Queens Nandi, Mkabayi KaJama, and other legendary chieftains. “My creativity is only possible by communicating with visions, feeling my ancestors spirits, and expressing my dreams,” explains Nadabuko, who’s especially proud of his sculptured Queen Nandi, the strong-willed mother of the fabled Shaka (King of the Zulus), described by historians as a 19th Century Aphrodite. Insisting “connecting with past greatness is my calling,” he adds, “Impregnated out of wedlock, she persevered, she’s an eternal symbol of hope.” Sculpturing has been a long romance for this soft-spoken artist. Once it meant leaving school books in his hut, and surreptitiously going to river banks to collect white or deep-red clay (Ibomvu). It was easy to manipulate, to sculpt miniature cows, houses, and other play things.

Describing the rebelliousness that fueled these secret forays, Ndabuko sighs, “Art scared the dominant white class. In my village black people weren’t supposed to paint, only work on farms, in the garden. Art was an expression of freedom. A threat, it was forbidden.” Clay was his escape from goats and sheep owned by his grandfather Masobeshe (who was also a sculptor), his defiantly questioning “senseless barriers, the primitive restrictions on my imagination.” Faced with these strictures, Ndabuko found a place to hide. He retreated to books during school, drawing in them, sketching pictures of a classmate, Phinele, a black-haired girl who sat close to him.

She laughed at him, thinking he was “crazy.” “I kept drawing her in my books,” he laughs, looking for “special blue” bone chips in his studio, a “safe haven” crammed with bottle caps, tires, and other discarded materials found on streets in Alexandra, an impoverished section of Johannesburg. “She just giggled, wondering if i had lost my mind. I thought she was beautiful…loved her so much, my books were filled with drawings of her.” That spelled trouble. Those sketches were ultimately discovered. Ndabuko was constantly being tongue-lashed in primary school, reminded the “devil” was inside him. Art and creativity still kept “whispering” to him, “strengthened” him enough to absorb the blows. But his Luthaayi high school teachers were equally resolute. Bound by rural superstitions, they felt Ndabuko’s evil spirits had to be exorcised. “Stupid artist, artist, look at that dummy….oooooh, the devil has him,” the cruel cries rang out, once Ndabuko was escorted to the assembly hall. Worse than a tree branch whipping, the taunts “humiliated” him. It’s still a searing memory. One that actually strengthened the teenager’s resolve to pursue music, sculpturing, and to connect with his beloved ancestors.“Art, no matter what the obstacles, is so important…it leaves a footprint and a message for the next generation…a gift they will inherit,” explains Ndabuko, his eyes brightening after talking about the “hurt” experienced at school.

“Creativity, the culture of my ancestors, was passed to me…a gift…It speaks to my sense of belonging. I do my work to remind the Nguni people about their culture. In Africa identity is everything.”Convinced his path had been chosen for him, he mastered the art of healing, believing “a connection with enough light (ukukhanyisa)” allows him to perform sacred rituals. The son of a truck driver (who lost his job while Ndabuko was a teenager), and a self-employed seamstress, he felt his parents needed his financial help. That kept him in the rural province, but he eventually sought “greener pastures” in Durban, and then did odd jobs in Johannesburg (1999). Throughout these lean years, Ndabuko often traveled to the Ukhahlamba Drakensberg Mountains to bolster his spiritual beliefs. At 6,562 to 11,424 feet, close to Lesotho on South Africa’s southern border, these cave-riddled “Dragon Mountains” were a refuge for Zulu warriors. They also fought and died here. Hoping to connect with their spirits–especially with their “blood”–Ndabuko often takes his guitar to this region to find inspiration for his music. Here he can “speak out loud to my ancestors.” “I need to go there, a lot, to find blessings,” confesses Ndabuko, who assembled his first guitars with tin and wires while tending to his grandfather’s livestock. He performs in clubs, and has recorded several albums (Maskandi love songs like Isoka Lintombi, about a woman having multiple relationships, and Ngangibala Matshe, a suitor lying about his owning cows to a woman).

Hiking through this rugged terrain, he’d connect with a blissful “essence,” eternal values hinting at the “Cycle of Life.” Freedom, Ndabuko’s sculptured confection of discarded bottle caps ambitiously tries to capture these virtues. Taking scraps (bone chips, wood chips, cloth) and giving them new meaning with a blazing, golden-toned face is meant to stir his ancestors’ hopes, evoke a future with true liberation and equality. His three assistants, Tebogo, Sphinx, and Thando, do most of the scavenging for those scraps. “I want them to learn, to grow, to create the unknown,” says Ndabuko, adding that he pays them for their help.

“We are Africans, we like using recyclables…we are raw and rough, sustaining the planet. It’s difficult work, and we must be on the alert for nails, sharp objects, but we come to safety, we must go through hardships to find new light.” Admitting those repurposed materials are a “complex” contemporary art medium–and certainly unfamiliar to many observers–Ndabuko encountered many rejections from galleries five years ago. Possibly too reminiscent of South Africa’s Apartheid Period, the spiritual intensity of his sculptures went unappreciated (“I suffered, had many self-doubts”). Or, they were too reflective of race in a society where racism is still deeply embedded.

His Sangoma healing, throwing bones in Zulu rituals to help people overcome family and health crises, helped ease some of his worries in the late 1990s. To be an effective healer, he couldn’t just think of himself. He somehow had to win the full trust of those seeking relief, and find “the light to connect” with them. “That intimacy involves a very complex set of emotions,” he admits, describing his becoming a “messenger,” a spiritual connection to sufferers’ ancestors–and to his own.“Sangoma is not a hobby you choose for yourself. It’s a calling coming from my ancestors. Whatever I tell people after throwing bones, my providing solutions, all this comes from their ancestors connecting with mine.” Ancestry is all-important to Ndabuko. It’s a reverence that sustains his creativity, inspires him to write a song like Izizwe. A tribute to Zulu kings, queens, and other heroes who fought to be free, this work fiercely uges black Africans to be proud, to resist all forces of imprisonment. It’s a plea poignantly reflected in his sculptures. They mirror the Zulu’s nobility, their celebration of the feminine aesthetic (in direct opposition to the stereotypical notion of women as evil witches and unfaithful wives). In this view Ndabuko is representative of the new African Renaissance, thinking that honors females as resilient and powerful voices in male-dominated Zulu society.

“The freedom of women is rarely discussed,” he sighs, pointing to his Freedom/Cycle of Life sculpture in his cluttered garage-turned-studio. “This is my way of motivating…women should be totally free.”Dismayed, but hoping to start a Mkabi kaNzunza sculpture (completing a work usually demands two months), he “cleanses” himself by speaking to his ancestors. He burns incense, then expects “revelations” to appear to him. Once they do, he selects a piece of pine wood, decides what other materials to use (often bones, cloths, nails, clays), and formulates the color palette. Mkabi kaNzunza is a sad yet clever queen in Zulu history, and to bring her back to life Ndabuko will use carefully-curated pinewood which is primed with white paint. He’ll add other pieces of paint to give the sculpture depth and texture. The wife of domineering chief Senzangakhona, she is often forgotten. Endowing her with an expressive, impeccably-detailed face will reanimate her. Other works in his makeshift studio tell equally-poignant stories. They give the garage a palpable sense of a living memorial, a shrine to deep, still-throbbing bloodlines. Honoring a force in his own life, a woman who is lovingly described as a “super grandmother” with 13 grandchildren, Nomsebenzi is glowingly patterned in resplendent colors. “A powerful woman with great knowledge, she passed all her learning to little ones,” extols Ndabuko, fervently. “I had many conversations with her, and wanted to honor her inner beauty with meaningful eyes and lots of blues to signify peace and the calm skies that are always visible in Africa.”

Portraying Africanism, its timeless embodiment in Zulu traditions, is his constant focus. His artistic raison d’etre. Believing women best symbolize the strength, the grace of his people, he feels his uBuhle Bakwa Zulu work captures the “love and unity” heartbeat of this Nguni ethnic group. His first attempt at sculpture, this colorfully-patterned face reflects self-assuredness, the power to survive. “It’s our identity,” insists Ndabuko, “pride in my nation.” Before leaving for a recording session, he points to a piece crafted from car tires, sewings, and cuttings in the indigenous Zulu style of Umbhadada sandals. It is colorful and eminently dignified, a sculpture inspired by the sandal’s humble beginnings as “a son of the soil.”

Invigorated by his origins, and unswervingly dedicated to expanding their contemporary appeal, Ndabuko insists, “the Gods called me. I embody these spirits, so there are many layers of importance to my work. The subtle beauty of our roots, the many colors vital to Zulus, the strong symbols of honor we have. I just want to preserve all this…. show others all the powers we have as Africans.”

By Edward Kiersh